Jane Street's 'Figurine Figuring' puzzle solution and a tricky follow-up question

Jane Street posted a Christmas-themed puzzle in January 2021:

Jane received 78 figurines as gifts this holiday season: 12 drummers drumming, 11 pipers piping, 10 lords a-leaping, etc., down to 1 partridge in a pear tree. They are all mixed together in a big bag. She agrees with her friend Alex that this seems like too many figurines for one person to have, so she decides to give some of her figurines to Alex. Jane will uniformly randomly pull figurines out of the bag one at a time until she pulls out the partridge in a pear tree, and will give Alex all of the figurines she pulled out of the bag (except the partridge, that’s Jane’s favourite).

If n is the maximum number of any one type of ornament that Alex gets, what is the expected value of n, to seven significant figures?

So we draw randomly from the collection of 78 days-of-Christmas figurines, stopping immediately when the partridge is drawn. We must find the average maximum count of any type of figurine across all possible draws. I’ll denote this expected value $\mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{12}]$ (the subscript 12 denotes the number of days of Christmas).

Initially I didn’t have any good idea about how to calculate or approximate this value. I tentatively guessed it might be about half the number of days, $\frac{d}{2}$, so roughly $6$.

My hand-wavy justification was that, across all draws, there’s an equal probability of drawing the partridge on any turn so collections of each size are equally likely. A collection might overlap some or all of the $d$ types of figurines with equal probability. In each collection, only half the types of figurine (six geese, seven swans, etc.) could occur more than $\frac{d}{2}$ times or more (and $\frac{d}{2} - 1$ fewer than this).

Regardless of whether this line of reasoning is valid, it turns out to be a reasonably good guess!

I’ll show how I solved the original puzzle and then ask what the limit is as the number of days $d$ increases:

\[\lim_{d \to \infty } \frac{ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{d}] }{d}\]A limit of $\frac{1}{2}$ seems possible, though I couldn’t get a handle on proving it. I’ll briefly describe a few ways I started to explore the problem. If you know a way to compute this limit, I’d be interested to hear from you.

Solution to Jane Street’s puzzle

The original puzzle asks for the value of $\mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{12}]$.

It’s clear that this value will be between 0 (we draw the partridge on our first turn) and 12 (we manage to draw all 12 drummers before we draw the partridge).

It’s also clear that there are $78!$ (more than $10^{115}$) possible draws of all figurines, so attempting any brute-force solution is a non-starter.

As noted in the introduction, across all $78!$ possible sequences there is an equal number of sequences with the partridge in any of the 78 possible positions. This means that drawing 5 figurines, say, is exactly as likely as drawing 75 figurines. Both size draws occur with probability $\frac{1}{78}$.

These numbers are all quite big, so let’s work with fewer days of Christmas to get a feel for the problem.

What about $\mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{1}]$? There’s a single partridge and no other figures, so the answer is $0$.

Not very interesting, so let’s add the two turtle doves and look at $\mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{2}]$. Now there are three figurines in total and $3!$ possible draws:

\[P_1, T_1, T_2\\P_1, T_2, T_1\\ T_1, P_1, T_2\\ T_2, P_1, T_1\\T_1, T_2, P_1\\ T_2, T_1, P_1\]There are two draws with no turtle-doves, two with a one turtle-dove, and two with two turtle-doves. As mentioned above, each size of draw is equally likely (the probability is $\frac{1}{6}$) so:

\[\mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{2}] = 0 \cdot \frac{2}{6} + 1 \cdot \frac{2}{6} + 2 \cdot \frac{2}{6} = 0 + \frac{1}{3} + \frac{2}{3} = 1\]As well as providing a tiny scrap of evidence to support my guess at the answer, this example shows that if we can count how many times we attain a specific maximum of figurine types across all draws, then we have a route to finding $ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{d}] $.

What do I mean by this? Let’s go to 5 Days of Christmas and look at finding $ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{5}] $.

How to count

Now there are $15$ figurines in total and so $14!$ possible draws where we don’t see the partridge. Suppose we want to count the number of draws of size $4$ where the maximum of any one type of figurine we see is exactly $3$. This could be done by choosing:

- any three of the 3 French hens and exactly one of the 2 turtle doves, 4 calling birds or 5 gold rings, or

- any three of the 4 calling birds and exactly one of the 2 turtle doves, 3 French hens or 5 gold rings, or

- any three of the 5 gold rings and exactly one of the 2 turtle doves, 3 French hens or 4 calling birds.

We want to calculate:

\[\binom{3}{3} \left[ \binom{2}{1} + \binom{4}{1} + \binom{5}{1} \right] + \\ \binom{4}{3} \left[ \binom{2}{1} + \binom{3}{1} + \binom{5}{1} \right] + \\ \binom{5}{3} \left[ \binom{2}{1} + \binom{3}{1} + \binom{4}{1} \right]\]This works out to be $141$ ways of drawing exactly four figures and seeing exactly 3 of any one type of figure in each draw.

If we do the calculation for all other sequence lengths from 1 to 14 (the largest draw without seeing a partridge), we can count the total number of ways of getting a maximum of exactly three of any type of figure. With these counts, we can compute probabilities and then the expected value.

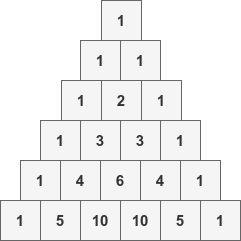

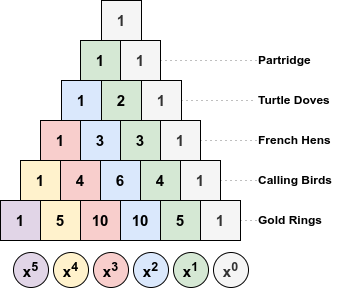

How can we count more systematically? Recall that entries of row $N$ of Pascal’s triangle show us the number of ways of choosing $k$ items from a total of $N$:

For a given row $N$, let’s set each entry $\binom{N}{k}$ as the coefficient of $x^k$ in a polynomial. For example for $N = 2$ the resulting polynomial is $1x^2 + 2x^1 + 1x^0$.

This is a standard way to associate the number of ways to draw, $\binom{2}{k}$, and the number of possible sizes of draws, $k$, in the polynomial. If we do this for other rows and create other polynomials, then multiplying them gives us a new polynomial associating possible draw sizes and the number of different ways that draw can happen.

So if we use at most 3 of each of these figurines, we can count number of possible draws of each possible length by truncating the rows of the triangle and multiplying the four polynomials (one for each type of figurine):

\[\left(x^{2} + 2 x + 1\right) \left(x^{3} + 3 x^{2} + 3 x + 1\right) \left(4 x^{3} + 6 x^{2} + 4 x + 1\right) \\ \left(10 x^{3} + 10 x^{2} + 5 x + 1\right) \tag{1}\]Multiplied out, this is the polynomial:

\[40 x^{11} + 300 x^{10} + 1020 x^{9} + 2084 x^{8} + 2856 x^{7} + 2769 x^{6} + \\ 1946 x^{5} + 995 x^{4} + 364 x^{3} + 91 x^{2} + 14 x + 1\]It tells us that, for example, there are 995 ways of drawing four figurines and having at most three of any type of figurine.

It’s almost what we need to solve the puzzle. To count how many of these draws have exactly three of any type of figurine, we’ll subtract the counts of draws of each length that have at most two of any type of figurine.

\[\left(x^{2} + 2 x + 1\right) \left(3 x^{2} + 3 x + 1\right) \left(6 x^{2} + 4 x + 1\right) \left(10 x^{2} + 5 x + 1\right) \tag{2}\]Which is equal to:

\[180 x^{8} + 750 x^{7} + 1338 x^{6} + 1351 x^{5} + 854 x^{4} + 349 x^{3} + 91 x^{2} + 14 x + 1\]The polynomial we want is $(1) - (2)$:

\[40 x^{11} + 300 x^{10} + 1020 x^{9} + 1904 x^{8} + 2106 x^{7} + 1431 x^{6} + 595 x^{5} + 141 x^{4} + 15 x^{3}\]As expected, we have $995 - 854 = 141$ possible draws of length 4.

To get the probability that the maximum of any type of figurine in the draw is exactly 3, we divide each term by some other numbers:

\[\frac{1}{15} \left( \frac{40 x^{11}}{\binom{14}{11}} + \frac{300 x^{10}}{\binom{14}{10}} + \frac{1020 x^{9}}{\binom{14}{9}} + \frac{1904 x^{8}}{\binom{14}{8}} + \frac{2106 x^{7}}{\binom{14}{7}} \\ + \frac{1431 x^{6}}{\binom{14}{6}} + \frac{595 x^{5}}{\binom{14}{5}} + \frac{141 x^{4}}{\binom{14}{4}} + \frac{15 x^{3}}{\binom{14}{3}} \right)\]The $\frac{1}{15}$ is the probability that our draw is of a given size $k$, and $\binom{14}{k}$ counts the total number of draws of size $k$ from the 14 figurines (all figurines excluding the partridge).

Summing these coefficients gives us a probability $0.20817$.

Coding the solution

We now know how to count draws with a maximum figurine-type count, and then turn these counts in probabilities. From here, it is straightforward to compute the expected value and solve the puzzle. Here’s some Python code (using the SymPy library) to do this:

import itertools

import sympy

from sympy.abc import x

def difference(seq):

"Return differences between consecutive elements of sequence"

ret = [seq[0]]

for i in range(1, len(seq)):

ret.append(seq[i] - seq[i-1])

return ret

def solve_puzzle(days):

"Solve Figurine Figuring puzzle for the given number of days"

total_figurine_count = days * (days+1) // 2

# Pascal's Triangle between row 2 and row `days`.

triangle = [sympy.binomial_coefficients_list(day) for day in range(2, days+1)]

# First compute polynomials counting draws with *at most* n figurines of any type.

polys_at_most = []

for day in range(1, days+1):

truncated_polys = [sympy.Poly.from_list(row[~day:], x) for row in triangle]

poly = sympy.prod(truncated_polys)

polys_at_most.append(poly)

# It's faster to extract coeffs to a list than to subtract sympy.Poly objects.

# The list is reversed and truncated so we have coefficients for x**1, x**2, ...

coeffs_at_most = [poly.all_coeffs()[::-1][1:] for poly in polys_at_most]

exact_counts = []

for seq in itertools.zip_longest((*coeffs_at_most), fillvalue=0):

diff = difference(seq)

exact_counts.append(diff)

# We now have integers in a 2D array of shape (total_figurine_count, days).

# Calculate expectation: sum(k*p(k) for 1 <= k < total_figurine_count).

expectation = 0

for draw_size, counts in enumerate(exact_counts, start=1):

counts = sum(count * max_ for max_, count in enumerate(counts, start=1))

expectation += counts / sympy.binomial(total_figurine_count - 1, draw_size)

return expectation / total_figurine_count

Calling solve_puzzle(12) gives us the exact (rational) solution for 12 Days of Christmas:

To the seven significant figures required by Jane Street, this is $ 6.859787 $.

What about the limit?

As I mentioned above, my estimate was for the expected value of the maximum count amongst the drawn figurines to be around $\frac{12}{2} = 6$. The actual value of $6.859787…$ is not far off, but it’s not close either.

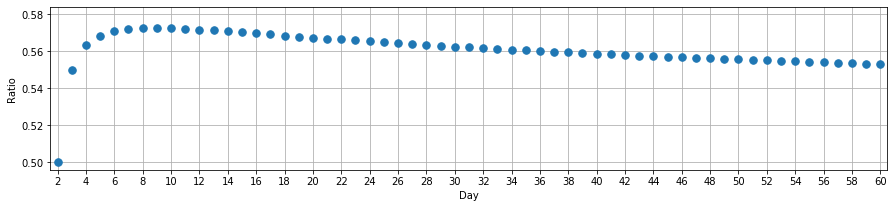

Does the ratio of expected value over days get closer $0.5$ as the number of days increases? Here’s a table showing a subset of results up to day 60:

| Day | Expected Value | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| 3 | 1.65 | 0.55 |

| 4 | 2.252778 | 0.563194 |

| 5 | 2.842180 | 0.568436 |

| 8 | 4.579894 | 0.572487 |

| 9 | 5.153015 | 0.572557 |

| 10 | 5.723870 | 0.572387 |

| 12 | 6.859787 | 0.571649 |

| 20 | 11.34742 | 0.567371 |

| 30 | 16.87542 | 0.562514 |

| 40 | 22.34634 | 0.558659 |

| 50 | 27.77765 | 0.555553 |

| 60 | 33.17920 | 0.552987 |

Plotting the Ratio column we see this:

For day two, we have a ratio of exactly $0.5$. From there, it increases until day nine, before slowly decreasing.

- Does the sequence continue to decrease monotonically?

- Does the sequence converge? Does it converge to $0.5$, or something else?

Unfortunately, I can’t work out the answers to these questions, or even calculate values (accurately) for days much further than 60 (multiplying polynomials with huge rational coefficients gets expensive, however much you try optimise the approach).

Final thoughts

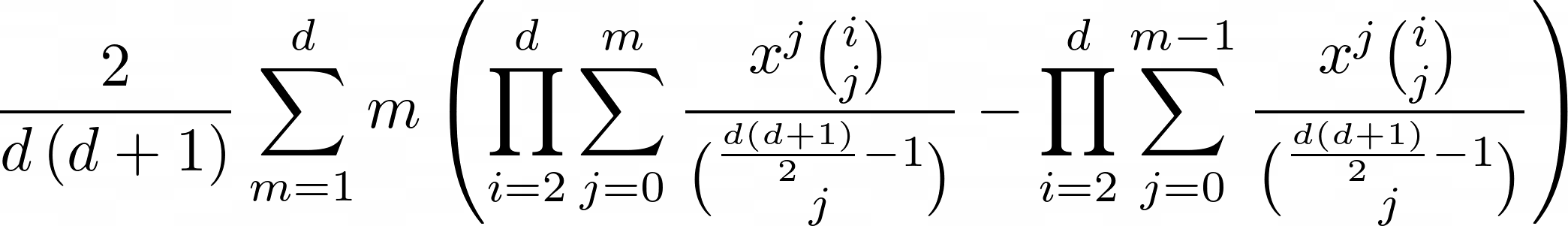

To calculate $ \mathop{\mathbb{E}}[\text{M}_{d}] $, a formula (unless I’ve made a mistake) is:

You can see the polynomial subtraction in the inner brackets. The summation of coefficients over $m$ is for each possible maximum count (giving us the expected value).

This is difficult (or even impossible?) to write in a way that admits an evaluation of the limit, and also seems difficult to approximate with simpler expressions.

Computing the product of truncated binomial coefficient rows (there’s OEIS A145324 for $(1 + 2x)(1 + 3x)...(1 + nx)$ but nothing general). The binomial coefficients could be bounded or simplified in some way (e.g.\ $\binom{n}{k} \approx \frac{n^k}{k!} $), but then there’s still the problem of summing over values in the restricted partitions of an integer.

Perhaps there’s an alternative approach to solving the puzzle, but I’ve not found it yet. If I make any meaningful progress, I’ll update this post.