A basic introduction to NumPy's einsum

The einsum function is one of NumPy’s jewels. It can often outperform familiar array functions in terms of speed and memory efficiency, thanks to its expressive power and smart loops. On the downside, it can take a little while understand the notation and sometimes a few attempts to apply it correctly to a tricky problem.

There are quite a few questions on sites like Stack Overflow which about what einsum does and how it works, so this post hopes to serve as a basic introduction to the function and what you need to know to begin using it.

What einsum does

Using the einsum function, we can specify operations on NumPy arrays using the Einstein summation convention.

Suppose we have two arrays, A and B. Now suppose that we want to:

- multiply

AwithBin a particular way to create new array of products, and then maybe - sum this new array along particular axes, and/or

- transpose the axes of the array in a particular order.

Then there’s a good chance einsum will help us do this much faster and more memory-efficiently that combinations of the NumPy functions multiply, sum and transpose would allow.

As a small example of the function’s power, here are two arrays that we want to multiply element-wise and then sum along axis 1 (the rows of the array):

A = np.array([0, 1, 2])

B = np.array([[ 0, 1, 2, 3],

[ 4, 5, 6, 7],

[ 8, 9, 10, 11]])

How do we normally do this in NumPy? The first thing to notice is that we need to reshape A so that we can broadcast it with B (specifically A needs to be column vector). Then we can multiply 0 with the first row of B, multiply 1 with the second row, and 2 with the third row. This will give us a new array and the three rows can then be summed.

Putting this together, we have:

>>> (A[:, np.newaxis] * B).sum(axis=1)

array([ 0, 22, 76])

This works fine, but using einsum we can do better:

>>> np.einsum('i,ij->i', A, B)

array([ 0, 22, 76])

Why better? In short because we didn’t need to reshape A at all and, most importantly, the multiplication didn’t create a temporary array like A[:, np.newaxis] * B did. Instead, einsum simply summed the products along the rows as it went. Even for this tiny example, I timed einsum to be about three times faster.

How to use einsum

The key is to choose the correct labelling for the axes of the inputs arrays and the array that we want to get out.

The function lets us do that in one of two ways: using a string of letters, or using lists of integers. For simplicity, we’ll stick to the strings (this appears to be the more commonly used of the two options).

A good example to look at is matrix multiplication, which involves multiplying rows with columns and then summing the products. For two 2D arrays A and B, matrix multiplication can be done with np.einsum('ij,jk->ik', A, B).

What does this string mean? Think of 'ij,jk->ik' as split in two at the arrow ->. The left-hand part labels the axes of the input arrays: 'ij' labels A and 'jk' labels B. The right-hand part of the string labels the axes of the single output array with the letters 'ik'. In other words, we’re putting two 2D arrays in and we want a new 2D array out.

The two arrays we’ll multiply are:

A = np.array([[1, 1, 1],

[2, 2, 2],

[5, 5, 5]])

B = np.array([[0, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 0],

[1, 1, 1]])

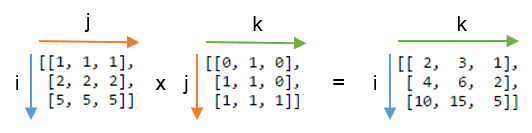

Drawing on the labels, our matrix multiplication with np.einsum('ij,jk->ik', A, B) looks like this:

To understand how the output array is calculated, remember these three rules:

- Repeating letters between input arrays means that values along those axes will be multiplied together. The products make up the values for the output array.

In this case, we used the letter j twice: once for A and once for B. This means that we’re multiplying each row of A with each column of B. This will only work if the axis labelled by j is the same length in both arrays (or the length is 1 in either array).

- Omitting a letter from the output means that values along that axis will be summed.

Here, j is not included among the labels for the output array. Leaving it out sums along the axis and explicitly reduces the number of dimensions in the final array by 1. Had the output signature been 'ijk' we would have ended up with a 3x3x3 array of products. (And if we gave no output labels but just write the arrow, we’d simply sum the whole array.)

- We can return the unsummed axes in any order we like.

If we leave out the arrow '->', NumPy will take the labels that appeared once and arrange them in alphabetical order (so in fact 'ij,jk->ik' is equivalent to just 'ij,jk'). If we want to control what our output looked like we can choose the order of the output labels ourself. For example, 'ij,jk->ki' delivers the transpose of the matrix multiplication (notice that k and i were switched in the output labelling).

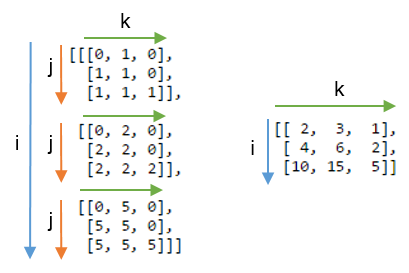

It should now be easier to see how the matrix multiplication worked. This image shows what we’d get if we didn’t sum the j axis and instead included it in the output by writing np.einsum('ij,jk->ijk', A, B)). To the right, axis j has been summed:

Note that with np.einsum('ij,jk->ik', A, B), the function doesn’t construct a 3D array and then sum, it just accumulates the sums into a 2D array.

A handful of simple operations

That’s all we need to know to start using einsum. Knowing how to multiply different axes together and then how to sum the products, we can express a lot of different operations succinctly. This allows us to generalise problems to higher-dimensions relatively easily. For example, we don’t have to insert new axes or transpose arrays to get them to line up correctly.

Below are two tables showing how einsum can stand in for various NumPy operations. It’s useful to play about with these to get the hang of the notation.

Let A and B be two 1D arrays of compatible shapes (meaning the lengths of the axes we pair together either equal, or one of them has length 1):

| Call signature | NumPy equivalent | Description |

|---|---|---|

('i', A) |

A |

returns a view of A |

('i->', A) |

sum(A) |

sums the values of A |

('i,i->i', A, B) |

A * B |

element-wise multiplication of A and B |

('i,i', A, B) |

inner(A, B) |

inner product of A and B |

('i,j->ij', A, B) |

outer(A, B) |

outer product of A and B |

Now let A and B be two 2D arrays with compatible shapes:

| Call signature | NumPy equivalent | Description |

|---|---|---|

('ij', A) |

A |

returns a view of A |

('ji', A) |

A.T |

view transpose of A |

('ii->i', A) |

diag(A) |

view main diagonal of A |

('ii', A) |

trace(A) |

sums main diagonal of A |

('ij->', A) |

sum(A) |

sums the values of A |

('ij->j', A) |

sum(A, axis=0) |

sum down the columns of A (across rows) |

('ij->i', A) |

sum(A, axis=1) |

sum horizontally along the rows of A |

('ij,ij->ij', A, B) |

A * B |

element-wise multiplication of A and B |

('ij,ji->ij', A, B) |

A * B.T |

element-wise multiplication of A and B.T |

('ij,jk', A, B) |

dot(A, B) |

matrix multiplication of A and B |

('ij,kj->ik', A, B) |

inner(A, B) |

inner product of A and B |

('ij,kj->ikj', A, B) |

A[:, None] * B |

each row of A multiplied by B |

('ij,kl->ijkl', A, B) |

A[:, :, None, None] * B |

each value of A multiplied by B |

When working with larger numbers of dimensions, keep in mind that einsum allows the ellipses syntax '...'. This provides a convenient way to label the axes we’re not particularly interested in, e.g. np.einsum('...ij,ji->...', a, b) would multiply just the last two axes of a with the 2D array b. There are more examples in the documentation.

A few quirks to watch out for

Here a few things to be mindful/wary of when using the function.

einsum does not promote data types when summing. If you’re using a more limited datatype, you might get unexpected results:

>>> a = np.ones(300, dtype=np.int8)

>>> np.sum(a) # correct result

300

>>> np.einsum('i->', a) # produces incorrect result

44

Also einsum might not permute axes in the order inteded. The documentation highlights np.einsum('ji', M) as a way to transpose a 2D array. You’d be forgiven for thinking that for a 3D array, np.einsum('kij', M) moves the last axis to the first position and shifts the first two axes along. Actually, einsum creates its own output labelling by rearranging labels in alphabetical order. Therefore 'kij' becomes 'kij->ijk' and we have a sort of inverse permutation instead.

Finally, einsum is not always the fastest option in NumPy. Functions such as dot and inner often link to lightening-quick BLAS routines which can outperform einsum and certainly shouldn’t be forgotten about. The tensordot function is also worth comparing for speed. If you search around, you’ll find examples of posts highlighting cases where einsum appears to be slow, especially when operating on several input arrays (such as this GitHub issue).

Historical notes and links

The einsum function was written by Mark Wiebe. Here is a thread from the NumPy mailing list announcing its existence, followed by discussion about the motivation for introducing it into the library. In 2011, the function was included as part of NumPy 1.6.0.

Three further links that may be of interest: